This detailed planning document provides an overview of the school project I undertook for LSC 530, Texts and E-Tools for Tots and Teens, at the University of Rhode Island. For this project I “genrefied” a high school library in Massachusetts. “Genrefying” has been a topic that has interested me for many years; however, a project of this magnitude is hard to complete without dedicated and focused staff time. When LSC 530 students were given the choice to choose a school or community project, I knew this would be the perfect opportunity to merge theory with practice, applying the concepts and Learning Outcomes of the course to create something that would benefit thousands of high school students in the years to come.

Rationale

Texts and E-Tools for Tots and Teens focused on how media, of all types, impacts babies, children, and teens. For this project, teens and their relationship to young adult (YA) books was considered, specifically how a library’s fiction collection could be arranged so that teens can find books that meet their definition of “quality.” “Genrefying” means organizing books by subject, category, or genre so that patrons can find materials that interest them easier. Related to the BISAC method, or the Book Industry Standards and Communication, in which customers at bookstores or patrons at libraries browse books by category or subject title rather than by the Dewey Decimal System, it is an ideal way of organizing materials for people who are looking for a type of book rather than a specific title or author. By genrefying a high school library it helps teens find quality titles they may have never thought of trying. As Jack Martin, director of the Providence Public Library said, the best people to judge quality teen literature are the teens who are reading them (Hobbs, LSC530 Texts and Tools for Children and Youth, April 9, 2014). This helps librarians become more informed gatekeepers, aware of what their teen patrons want to read and developing the collection based on those needs. Instead of librarians being the judge of “high art” or “quality” literature, deeming what teens should be reading rather than what they actually want to read, shouldn’t librarians consider, “the form of a work and the enjoyment it brings,”(Verschoor, 2011)? Through genrefying the collection, it allows librarians to observe teens and the genres they flock to, it also specifies circulation statistics by showing what genres receive the most and least checkouts. Instead of purchasing books that you think your patrons will like, why not start ordering books you know teens will love!

In this course, we’ve read Kimberly Reynold’s text, Children’s Literature: a Very Short Introduction, which talked about the power of genres to aid in literacy of children. For ELA students or those reading at very low levels, genres can be used as a literacy tool to get these teens excited about reading as well. Reynolds (2011) said of genres, “the constraints of convention can be a spur to innovation, provoking writers to explore the possibilities for simultaneously conforming to and transcending genre expectations (p. 78). For teens who are struggling readers or having trouble connecting to the English language, the sense of familiarity genres afford, allowing students to “anticipate” plots and giving them, “confidence, stamina, and satisfaction” as they connect with books, is another benefit to organizing a fiction collection by genre. Teen readers, like children, may be drawn to certain genres, and rather than inhibiting their literacy skills, choosing books from the same genre can provide numerous benefits. Genrefying a fiction collection makes it easier for teens, and their teachers, to find books that may help them become better readers.

Virginia Walter (2010) talked about the importance of reader’s advisory in promoting reading (p. 30). Genrefying a library is a surefire way for librarians to know their collection and help them find books that meets a specific patron’s needs. Genrefying opens up so many opportunities for reader’s advisory. Through this process, librarians need to choose a genre for every title in their fiction collection. That means they have to read what each book is about. When students come to the library and ask for recommendations of books, there is so much knowledge to draw upon, and if no specific title comes to mind, the librarian can show the genre section that most relates to what they are looking for. Possibilities for reading maps, LibGuides, and book talks are endless with a collection organized by genre.

Throughout this project, I heavily relied on reader’s advisory websites like Goodreads, Amazon, and the database Books and Authors that provided me with clues to figure out which books belonged in which genre. What I found really useful were the professional reviews from places like the School Library Journal or Kirkus Reviews that are sometimes listed on these websites. They gave me additional genre clues and helped me learn more about titles. In this course, we talked about the power of review websites and what they can do for librarians. For my purposes, these reviews were very helpful for collection development and marketing. They gave me a wonderful base knowledge about hundreds of YA book titles so I can better help my patrons. These are a few ways this project aligned with the concepts and Learning Outcomes in this course. It provided me with extensive knowledge on the role media plays in the lives of teens, it taught me the variety of content available through YA books, and it helped me understand how to curate materials to meet teens specific wants and needs.

Context

If you have ever visited a high school library, one of the problems you might observe is the little time students have to search for a book. Another common problem for classes that require their students to choose a book for an assignment are the complaints from students who say they can’t find a book that interests them. However, what you’re likely to hear most from students are reader’s advisory questions where they ask the librarian to help them find a certain type of book, rather than a specific title or author. Here are some common questions:

- “I don’t really read, but I did like Where the Red Fern Grows in the fourth grade. Do you have any books like that?”

- “Do you have any mystery or horror books, something scary like Stephen King?”

- I like series books, like Percy Jackson and the Lighting Thief. Does the library have any series books like that?

These are the type of questions the school librarian and I, the library assistant, field regularly at Monty Tech, a high school with a student body population close to 1,200. Since the beginning of the school year, we have had many students ask us where they can find books like the Hunger Games, or mystery or horror books. With the exception of John Green and Ellen Hopkins, we have had few questions from teens asking us to find books by a certain author. The fiction collection is organized alphabetically so it was clear that our system could be designed in a way that would aid our patrons in finding books they like. Also, many teens, if they don’t find a book by browsing the expansive alphabetized collection leave without saying anything. There are patrons that ask for our help, but I’ve only seen a few actually look up books using the kiosk. Teens just have trouble finding the books they’re looking for. Genrefying was the best solution to connecting teens with the books they love.

The high school renovated their dark, dingy, and unoccupied library media center into a beautifully designed school library that students love. The current collection has a total of more than five thousand books, and the fiction collection makes up a little over 2000 of that. When I started working at Monty Tech at the beginning of the year, the school librarian and I were put in charge of ordering new materials, taking older materials out of storage, and arranging the new library. Aware of the needs of teens in school libraries, one of the ideas we had was genrefying the fiction collection. While the librarian did create foundational Google Docs to get the process started, the library was very busy with class visits, assisting students, and daily operations that the genrefying project took a back seat.

When a school or community project was proposed as an option for the final project in LSC 530, I knew this would be a great opportunity to apply what I was learning in class in a way that would benefit the students at Monty Tech. I asked the school librarian if I could take charge of the project for this course, and she was very receptive of the idea but questioned if it could be finished by the end of the semester. It was a project she was planning to take at least a few years to finish. I was confident it could be finished; not understanding how long a project of this size actually takes if only one person is working on it. I cataloged from home, chipped away bits and pieces at work when the library was slow, and stayed after work to the complete the project on time.

Aims and Goals

My goal is that we will see a significant increase in circulation by the same time next year. Many libraries that genrefy their collections say their circulation statistics increased by 30% within a few months. While I think this may be a bit slower in a school library because students have other schoolwork, I do think we should see results by the beginning of next year. This matters because a busy library is a funded library.

Another goal is to be able to physically see what genres we need to build up and those that need weeding. It is difficult to assess this when all the books are mashed up together. For instance, I believed science fiction was one of our biggest genres because those are the books I see cross the circulation desk most often. After the books were separated, the library didn’t have nearly as many science fiction books as I thought. Related to this goal, I hoped to figure out how the collection could be developed to attract male readers or the traditional “non-readers.”

My educational goals were to become more knowledgeable of YA literature throughout the project, learn about the popular content in YA materials, and use this information to curate a collection that meets teen’s definitions of “quality.”

One of my aims for the next year is to see more students using the school library to find books. Some of our teens are devoted to certain authors (like John Green or Ellen Hopkins), and the genrefying project will put similar books next to their favorite authors, hopefully introducing them to new books they may have never considered. For the non-readers who complain that there are no good books, categories that are created (like War, Sports, or Graphic Novels) may pique their interest. An alphabetized system can be intimidating for teens that don’t use or don’t know how to use library. Because of this, some students avoid the library entirely. If non-readers have a place to start, a place that informs them of the books they are about to pick up, perhaps they’ll find materials they will enjoy.

Stephanie Sweeney (2013), a secondary library teacher, wrote about her experience genrifying her library in YALSA saying, “The task required a great deal of planning and hard work, but I believe it has improved patron access by helping them be more independent searchers and discover new authors in genres they already favor” (p. 45). A patron of the Darien Public Library (2009) in Connecticut had this to say about the library’s new browsable model, “The books everywhere, but especially in the children’s room, have been shelved, labeled, and organized in a way that makes me feel less like a moron and more empowered to find what I’m looking for on my own.” A group of women who genrefied an elementary school library (2012) wrote, “Kids who’d previously had trouble choosing a book for independent or pleasure reading loved this new and easier-to-navigate arrangement.”

One of my biggest aims is to see patrons look for books on their own rather than come straight to the circulation desk asking for assistance. We love to help students find books to read, it’s actually the part of my job I like best, but the teens have been reluctant to use the computer kiosk to search for books, and because they weren’t exactly sure what they were looking for, it made it hard for teens to choose a book in the small amount of time they had to search. The goal is for students to become more independent searchers, feeling empowered that they can find their own books rather than needing to ask an adult for help.

Process Overview

The genrefication project had five major steps:

- Re-cataloging and assigning a genre to every print fiction title

- Print and tape the new genre spine label for each book

- Stick and tape a colored dot to each book signifying its genre

- Shelf the books alphabetically within their genre

- Create signage to display each genre

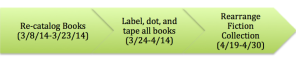

While the steps may seem very straight forward, each step took a significant amount of time. The fiction collection is made up of over 2000 books, so 2000 books needed to be re-cataloged, needed spine labels, dots, and tape, the books needed to be separated into the fourteen genres and then re-shelved. I needed to make attractive and interesting signage that clearly represented the genre. This was the original timeline:

This was the actual timeline:

The process was much more time consuming than I originally planned. Cataloging took me almost a full month longer, and I ended up labeling books with spine labels as I went to break up the monotony. With the conclusion of the project, I am confident that after time the aims and goals will be met, and possibly exceeded.

Process Details

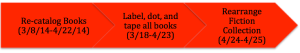

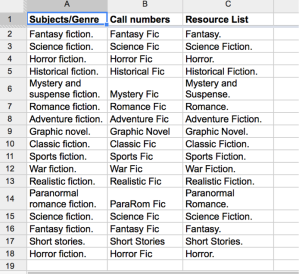

To begin, the school librarian and I chose the genres that would represent the collection. We chose fourteen genres and matched them with colors based on dots Demco and the Library Store had available. Here are the genres we selected and their corresponding colored dots:

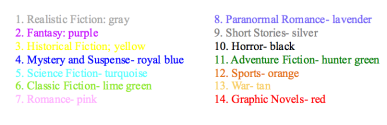

After the genres were chosen, the school librarian created two Google Docs to get the project underway. She created a Library Title & Copy List that I worked off of to make sure every title was re-cataloged.

Here is an image showing the list:

The other document the librarian created was a Subject Integrity List. She assigned a Call Number, Subject Heading, and Resource List heading for each genre so that when I was re-cataloging I could copy and paste from this document to ensure every new record was accurate. Here is the Subject Integrity List:

Watch this step-by-step process to see how I changed nearly 2000 records to reflect their genres:

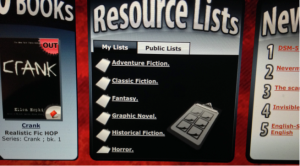

The call numbers were changed so new spine labels with the correct call numbers could be printed and later found on the shelves. The genre needed to be included among the subject headings so when patrons search a keyword in the catalog, like “Fantasy” or “Horror,” every book with that genre as a subject heading would be presented as an option for the patron. Finally, my favorite tool is the Resource Lists. When you select a subject list in the catalog for each book, you are creating a searchable list that patrons can browse for each genre.

Here is a picture of the Resource Lists that is available to search on the homepage of the school’s Follet Destiny Quest catalog:

I was able to re-catalog 30-35 records every hour, and with a total of 1926 records (not including duplicate copies) it took me around 65 hours to complete the catalog portion of this project.

In the timeline, I proposed that I would finish all cataloging before I began putting labels on the books. I decided to start the labeling process when I was halfway finished with the cataloging. Cataloging was something I could work on at home, but labeling had to be done in the library. This system worked pretty well and made the process more bearable. I did catch up to myself a few times, having to take a break from labeling to re-catalog more books.

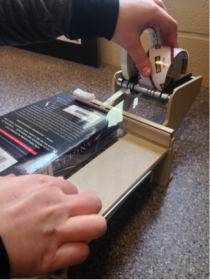

The first step with the labeling process was scanning the books directly into a barcode’s list, downloading the list, and printing out the spine labels. Because I took around 30 titles alphabetically from the book shelves at a time to receive a label, many books had the same call number (ex. FIC SOM). I had to scan each book to make sure the new genre spine label was assigned to the right book. Once the spine label was in place, I taped the label on, and if the book was paperback, I taped the entire binding to give the book more durability. The book was then placed back on the shelf in the order I took it down. Because this process took a while, it would have been impossible to seperate the books as I went, and the school librarian suggested I wait to put on the colored dots until closer to the project’s end.

Here are pictures of me scanning the book, sticking the label onto the spine, and securing the label and binding with tape:

After all of the labeling was completed, I stuck on the colored genre dots to match the genre of the books. Again, I took books off the shelf alphabetically, stuck on the dot, taped over the dot to secure it, and put the book back on the shelf in alphabetical order. Books were still not placed with their genre at this point.

Here is a picture of me putting a genre dot on a Fantasy book:

I finished cataloging, labeling, dotting, and taping on April 23, the Tuesday during April Vacation week.

Here is a picture of me in front of all of the cataloged and labeled books:

My original plan was to completely genrefy the collection before students came back to school after April break. I was able to accomplish this ahead of schedule. I had a helper assist me in combing through the labeled collection to organize books within their genres. We placed books in carts alphabetically so we didn’t have to arrange them again after they were put in their genrefied groups.

Here is a picture of the books being separated into their genres:

Here is a picture of me in front of all of the fiction books separated by genre on the tables:

The next step was re-shelving the books by genre based on the number of books in each category.

Books were arranged in this order:

1. Realistic Fiction

2. Fantasy

3. Historical Fiction

4. Mystery and Suspense

5. Science Fiction

6. Classic Fiction

7. Romance

8. Paranormal Romance

9. Short Stories

10. Horror

11. Adventure Fiction

12. Sports

13. War

14. Graphic Novels

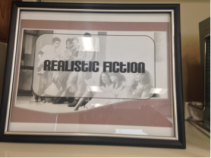

We had hundreds of Realistic Fiction books but only a few books on War. We elected to keep Graphic Novels at the end, separating them from the rest of the collection. At the beginning of each new genre I placed an 8X10 framed sign I had created to display the next genre. The fourteen signs made shelf space extremely limited, and I had to move books around quite a bit before everything fit just right.

Here are pictures of the genre signs I created:

Here is a sign that explains the new system to students:

We finished re-shelving the fiction collection at the Monty Tech school library on April 25, 2014, five days ahead of schedule.

Here is a picture of the completely genrefied library:

Assessment

A week of school has gone by since the library was genrefied. This isn’t a lot of time to do a formal assessment or study circulation statistics to see how the project has affected checkouts. Therefore, my assessment is based on student reactions to the project. On the first day back from April Vacation, the sign explaining the new system had not been printed. Instead of offering help to teens as they searched for books, I deliberately observed how they searched for books. Essentially, I wanted to see if they understood the system without having to read directions from a sign.

I observed three teens, two girls and one boy who frequent the library. They all noticed the difference immediately and walked up and down the rows of shelves trying to figure out what was going on. A light bulb seemed to click for each of them, and because I am familiar with their reading habits, I saw them begin browsing for books in their favorite genres. One girl was attracted to Realistic Fiction, the other girl to the Paranormal Romances, and the boy to Fantasy Fiction. Each of them found a book and checked one out. I asked them if they understood the new system and what they thought about finding new books with the new set up. One girl said, “I think having the books separated in genres will help because people will be able to find the books they like easier. Many people don’t know particular author names so that’s helpful.” The boy said, “I was confused at first, but I think it will be a lot easier now to find books.”

Based on my observations and student feedback, it was apparent that it took the teens a little while to figure out the new system. There were confused looks but there was definitely a point when they understood it. Once the students got to that point, it seemed like they were able to enjoy browsing books in their favorite section and find a book that interested them. Based on the boy’s comments, I made sure to have my sign with directions hanging in the library the next day. Most students spot the sign, but we can easily refer students to it if they have any questions.

On Thursday, an English teacher brought down two of her classes to choose a book for a paper they were assigned. She asked us ahead of time to pull titles that the teens may find interesting. This system made it so much easier to choose selections for students. I quickly made an, “If you liked Hunger Games…” section by searching the Science Fiction genre, I made a section for Twilight lovers by pulling books from Paranormal Romance, and I made five other section that would peak their interests in a matter of 20 minutes. Normally, I would have had to have a title in mind, search for it in the catalog, and then find it. With the new system, I was able to complete a reader’s advisory task in much less time.

What was most interesting, but not necessarily surprising, was how students from the two English classes gravitated towards particular sections. After I briefly explained to the classes how the new system worked, I showed them the direction sign, and let them begin browsing. They all visited the sign first to figure out what they wanted to read, and then found the genre among the shelves by spotting the genre sign. 90% of the boys flocked to the Sports and War genres, while many girls could be spotted in the Romance, Paranormal Romance, and Realistic Fiction sections. It was really helpful to see an example of this early on. Normally, we would have had 15 boys in the library asking the librarian and myself for sports books or survival books, or they would’ve grumbled that there was nothing to read. While we still heard a few grumbling students, most boys walked away with a book they found on their own.

After organizing the collection by genre, I was able to fulfill one of my goals by spotting the genres that needed severe developing. The Realistic Fiction collection has over 500 titles, the Sports section has less than 50, and the War genre only has 19 books. After having the two classes down for a visit, it is very clear that the library needs to purchase more sports, adventure, and war books because that is what most boys at our school prefer to read. When the collection was arranged alphabetically, we knew there were sports and adventure books but we didn’t know how many. Genrefying the library solved this problem.

There were a few changes I would make in retrospect if I were to undertake this project again. I was a little disappointed about was how much room the genrefying signs took up on the shelves. I wasn’t anticipating how little space we’d have left after the genres were organized. Because the school has a healthy book budget (we’re actually getting over 300 new fiction books in a few weeks), growth is a concern. We have less space to work with, so we need to do some weeding and will likely need to convert the signs to a 5X7 or buy another bookshelf to make room.

A project of this magnitude takes time, and it would be useful to have a team or student helpers work on this project simultaneously. Also, for a school library, the best time to complete a project like this is during the summer when you can take your time, make a mess, and put the library back together beautifully before anybody notices a difference.

Though there were bumps along the way, I learned so much through this process. I feel very fortunate that the school librarian let me take charge of a project this size and trusted my judgment on the layout of the fiction section. I learned so much about YA literature, how to provide better reader’s advisory services and develop the collection to meet teen’s versions of “quality.” Most of all, I am excited that I was able to complete a project that will be used by thousands of students in the years to come, making it easier for them to connect with the books they love.

References

Fister, B. (2009, October 1). The Dewey dilemma. Retrieved April 28, 2014, from http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2010/05/public-services/the-dewey-dilemma/

Kaplan, T. B., Dolloff, A. K., Giffard, S., & Still-Schiff, J. (2012, September 28). Are Dewey’s days numbered?: Libraries nationwide are ditching the old classification system. Retrieved April 28, 2014, from http://www.slj.com/2012/09librarians/are-deweys-days-numbered-libraries-across-the-country-are-giving-the-old-classification-system-the-heave-ho-heres-one-schools-story/

Reynolds, Kimberley (2011). Children’s Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Sweeney, S. (2013). Genrefy Your Library: Improve Readers’ Advisory and Data-Driven Decision Making. Young Adult Library Services, 11(4), 41-45.

Verschoor, B. (2013). Say hi to high, hello to low. Retrieved April 21, 2014, from http://www.arenastage.org/shows-tickets/sub-text/2011-12-season/the-book-club-play/hi-to-low.shtm

Walter, Virginia (2010). Twenty First Century Kids, Twenty First Century Librarians. Chicago: American Library Association.

Thank you so much for posting this in such wonderful detail. I am about to genre-fy my high school library’s fiction collection, and this information is so valuable.

Pingback: Genrefication of your school’s fiction collection « CMLE

Thank you for this! We are gentrified but the digital catalogue needs to be updated.. this will really help!

Did you ever post your circulation results from pre-genre-fy to post genre-fy? I’d be very interested to know how they improved. If at all possible please respond via email! Thanks so very much in advance!

Hello,

The former librarian genrified several years ago and we absolutely love it! One question though, I have to update the call numbers (they were not updated). Di you think the pattern:

Genre/FIC/author last name is the best order? I want to make sure I don’t have problems running an inventory of Fiction. Would I only be able to run an inventory of a genre.. not the entire fiction section? We use Follett.

Thanks!

Hi Molly. I’m working at a new school now and am in the process of genrefying that collection. I never had a problem reading a report from Follett with the call numbers in that order, it actually separates quite nicely and helps me see which genre gets the most/least checkouts. Instead of having a giant fiction category, it separates, for example, into Historic FIC and tells me how many books are in that category, and how many circs we had in that section. However, I never ran an inventory with the collection mentioned in this blog post. I’m assuming it arranges in the same way as the smaller reports, but I’ve never seen it myself. When my current project is complete I will look into this.

This is so helpful! Thank you. I have been thinking about doing this and I am even more motivated now. You mentioned some benefits that I hadn’t considered.

Hello! Will you pretty please confirm that this post was written by Christy Minton? Thank you!

Hello, yes this post was written by me, Christy Minton.

Pingback: Lib477B Fostering Reading Cultures in Schools | Jim Cartlidge